On perspective

In the context of primary architectural representational techniques, the perspective and its legacy could be credited to several advocates and inventors such as Brunelleschi, Leonardo Da Vinci, Alberti and so on. If specified to a timeframe, it could be respectfully coined to the treatises of the Quattrocento. Six-hundred years later, it is evident, more than ever that their legacy is alive and well flourishing. In this article, an exploration of the perspective as a visualization technique will be made, through various ways in which its use has been moulded and thought of throughout the past. Is there a correlation between architectural thought and the architectural image, or is it up to the interpretation of the author? and has the use of perspective reached its peak in the 21st century to become the new symbol of our architectural period? These questions will be covered by observing some exemplary reference perspectives from the present day to antiquity.

At the outset, a description of perspective is necessary in order to stress, as much as possible, its non-conventional sense. Perspective is the way one interprets or looks at something; it is a technique or a number of techniques combined; it is an impression in which shapes combine height, width, depth and position in relation to each other as well as the viewer to create a composition. Perspective then, can be understood as a photograph, a collage, a 3D software rendering, a painting or drawing just to mention a few.

Simultaneously, one must make reference to perspectives in terms of the 21st century and what it means today - to live in an increasingly image society, specifically with inventions of media and visual applications such as Instagram, Pinterest, Tumblr along with others. Consequently, we are exposed to perspectives each day by these applications, not-limited-to but particularly in designer/arts/photographer/architectural industries. These apps are current phenomenons for spreading visualizations. However, new platforms seem to call for renewed measures, meaning a variety of experimental techniques in representing a piece of work. Nowadays, we may witness attempts to unlearn the classical perspective, with what one could call abstraction and distortion, the use of collage and mixed media. Various young practices such as Fala Atelier are an example of the many that give advanced meaning to the legacy of perspective with contemporary means by digitalization.

Wanting to update a certain representational tool is not without precedent of course. Arguably, Brunellesci reinvented the techniques of Medieval paintings, where a notion of depth had clearly existed through the use of contrasting colours meanwhile object outlines did not correspond to their vanishing points. As an example, Giotto’s paintings paid importance to presenting three dimensional architectural elements with a sense of depth yet they were still naive in their abstractions. Hence, perspective as a measured technique was not used. It was Brunelleschi’s newly-found demonstration “how perspective is not simply the representation of three-dimensional space, but rather a mathematical construction that implies the possibility of making three-dimensional space itself measurable.” 1

In spite of its breakthrough, Brunelleschi’s scientifically correct method was problematic for the architects wishing to show-off their designs in one-point perspective. The technique still provided little depth to objects and mainly gave space for the atmospheres of the scenes, turning the centre of images into rather flat 2D elevations instead of the hoped 3-dimensional drawings. Furthermore, the popular symmetrical frontal-façade designs of the time gave little opportunity to make use of one-point perspective’s full potential. Despite the frustrations with uniform exterior elevations, the technique proved highly successful in terms of interior representations, especially in churches such as the Santa Maria presso San Satiro church in Milan. Interior spaces required grandness at low-costs, which required painters to create a trompe-l’oeil - an architectural optical illusion of vast space using one-point perspective on walls, mostly towards the apse/axis of the transepts. These paintings presented forced-perspectives which tricked the eye into believing in an impressive, full-scale space when viewed from a certain angle.

Moving on from the deceptive use of perspective, the technique was once again regenerated by Albrecht Dürer in 1525, adding to its legacy. Alongside his writing of the book - Instructions for Measuring with Compass and Ruler - the two-point perspective was invented. Architects were beginning to use perspective in their daily work, however the drawings produced were not utilized as a tool for design - only a visualization of their work. Regardless of his discovery, the new technique was also positioned as an inconvenient design tool towards the end of the Renaissance period. It continued to have the same reputation throughout the coming century.

Thus, in the 1700s, perspective became a picturesque imagery of designs and as a result it was nearly neglected even as a simple representative medium. It did not make much sense for architects to use a technique which did not display their talents fruitfully in the process of designing long and repetitive façades. Acknowledging the difference and division of painterly perspectives from the architectural discipline as a whole was reflected in the usage of the tool with the emergence of industrialism.

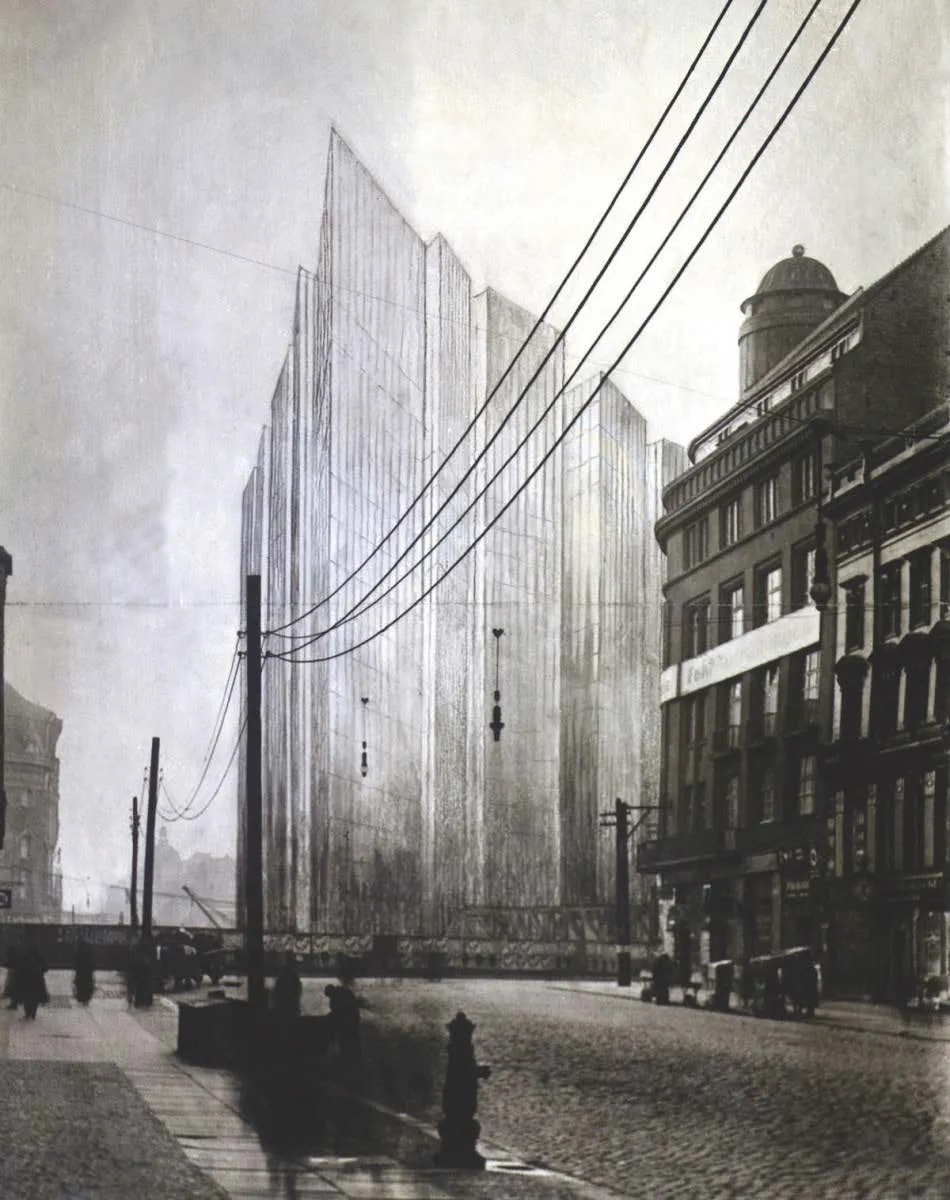

In the 1900s, momentous changes were taking place in design and architectural circles - breaking free from repetitive classical compositions. Hence, the two-point perspective finally found a broad usage amongst designers as a medium capable of transmitting ideas behind their buildings. For the first time, Modernism elaborated the domain of 3-dimensional drawing - specifically at a moment when architecture was becoming institutionalized and design schools were opening their doors for the first time. Consequently, the perspective as a representative tool progressed into a method of design while it became more and more dogmatic in modernist schools of architecture.

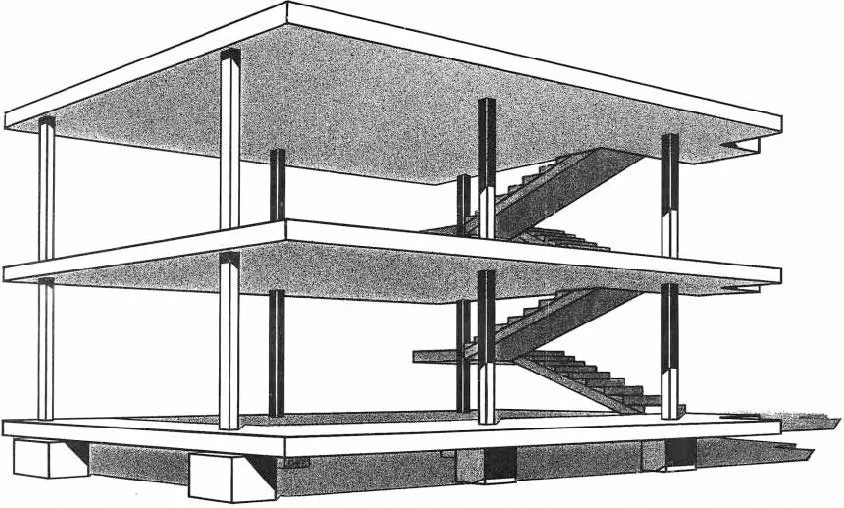

Observing the works of modernists such as Le Corbusier and Mies van der Rohe, it is evident that the use of perspective was at the forefront of their thinking process. When Le Corbusier drew the Maison Dom-Ino in a perspective view, why would he have thought of this pure technicality in a picturesque representation? and how many designers would associate and recognize the plan of it? It can be said that Le Corbusier aimed for a certain consent with the eye, therefore the perspective and its legacy could also be seen as a tool of compromise, where architecture vanished into the realm of reality. Additionally, this tool seemed reserved and only to be applicable in the world of architecture too as many of Le Corbusier’s paintings continued purist representations of the time.

Architects thought in perspective, drew in perspective, elaborated in perspective and even found perspective as a new language, a way to translate space in words to a drawing. The order of design being reversed - historically, this process began with idealised plans. Instead we begin with the perspective - an image in our mind - which may generate plans, sections and elevations. In this system, the use of perspective or the visualization itself becomes the primary starting point in conceiving an architectural concept.

Furthermore, the classical one- and two-point perspectives were seen as an obligatory instrument to be learnt as a crucial tool of representation in the first year of an architecture students’ education. While institutions in the past few decades have been exploring various new techniques. “CAD, BIM and CGI softwares use perspective views to communicate design ideas and these technologies clearly owe a great deal to the close study and application of perspective principles in the Renaissance.” 2 With the elaborations of such softwares, the perspective became more concrete, realistic and tangible as a communication tool - which some clients often seem to favour instead of the abstract collages - raising the question of the audience and whom an image is being made for. As a result, perspective is again seen as a representative tool, where materials and components of a building come together under one holistic understanding. Visualization offices such as ArtefactoryLab are an example of a practice which creates renderings for projects with the combination of real photographs of the site, in a mixed use of various rendering and editing programs.

These images are often hard-to-tell of their reality at first sight and are highly constructed. Taking a closer look, the realization of how far we’ve come in the legacy of architectural representation is impressive. Buildings no longer position themselves at centre-stage and image boundaries cut-off the actual proposal - stepping back as the author of the building and providing more generosity to the happenings of the scene - even if the view is of a road-refurbishment. Which does not try to hide but rather celebrates the imperfections of everyday life, thereby again, giving new meaning to the legacy of perspective.

Nevertheless, some institutions seem to be paying less importance to digitalization when it comes to perspectives. As an example, the studio of Prof. Adam Caruso in ETH Zurich is a course where astonishingly detailed physical models are produced by the hands of many architecture students, then photographed in a specific perspective view. Once again, making us naively ask if some of them are real-life scenes or not. These fabricated perspectives are usually interior shots, with the exception of a few exterior ones, this brings us to the question of turning a physical 3D object into a flat 2D image. Commonly, it is after a final critique that the photography of ‘portfolio-worthy’ models take place, however some institutions encourage the use of these images as atmospheric perspectives being part of the presentation itself. Then, are students and professionals making specific compromises when choosing a medium to represent a piece of work or is it up to a certain style? The aesthetically realistic renders or abstract quasi-collage perspectives are again representing an eternal division between institutional teaching and practices. Certainly, there is a definite beauty in the production of such physical models and having made them by hand perhaps allows for a slower absorption yet deeper understanding of different qualities of spaces. Architectural thought gaining from the process of perspective.

In conclusion, while investigating the subject matter and writing this text, we have discovered that the legacy of perspective is a legacy set up for change. It is not simply a visualization tool, it is a system set up for the possibility of transformations, additions and subtractions which continually leaves space for reinterpretations. Perspective as a tool can take on many roles - a starting point, a process, a finishing point or a straight-to-the-point visualization - however the underlying idea remains a constant while different interpreters repeatedly morph it. Architects and designers are now further examining the origins of perspective and its use throughout history, documenting them through various researches, exhibitions such as ‘Disappear Here’ at the RIBA in London and on podcasts such as ‘Drawing Matter - Talking to Drawings’ 3. It will be interesting to see where the future path of perspective might lead us after a post-digital era and in what ways exterior forces such as new media will influence the use of perspectives. Architects and designers are a large part of perspective’s past and continuing presence, therefore being part of its unmistaken legacy.

Adonel Myzyri, Viktoria Hevesi

2020

Written for Involved Magazine Issue 2 - Legacy

Images;

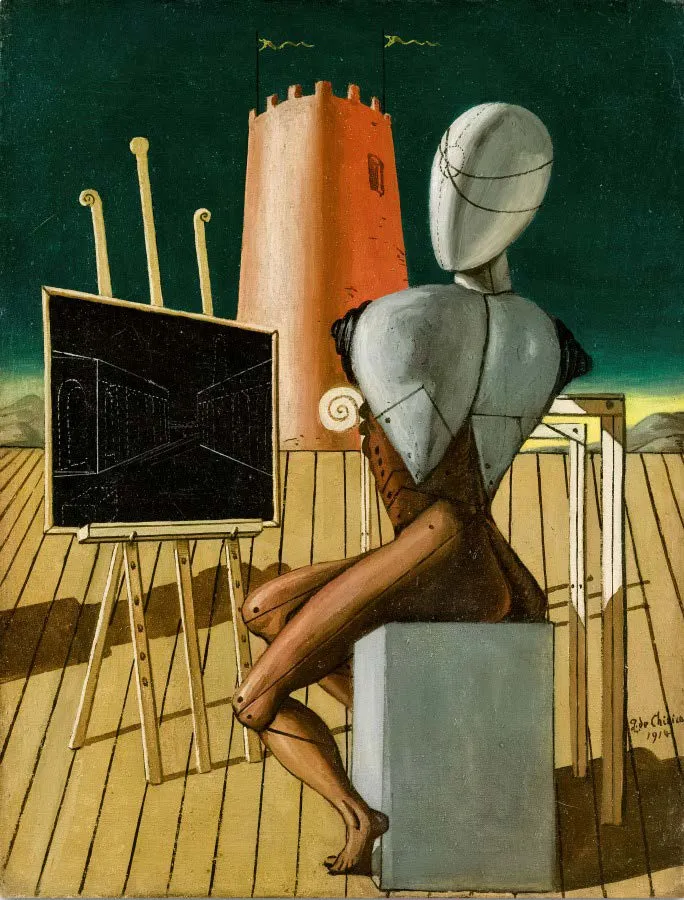

Il vaticinatore, Giorgio de Chirico

Delivery of the Keys, Pietro Perugino

Maison Dom-ino, Le Corbusier

ETH Zurich, Prof. Adam Caruso Studio

Artefactory Lab for Bruther + BAUKUNST

Friedrichstrasse, Berlin, Mies van der Rohe

- Pier Vittorio Aureli, ”Intangible and Concrete: Notes on Architecture and Abstraction” e-flux journal #64, April 2015, page 9.

- https://www.designingbuildings.co.uk/wiki/The_origins_of_perspective

- https://castbox.fm/channel/id1368647?utm_campaign=a_share_ch&utm_medium=dlink&utm_source=a_share&country=us

All images used in this research are the property of their respective owners. We do not claim any ownership or rights to these images. All rights are reserved by the original creators.