Linguistics of Drawings

Architecture and essentially it’s representation is made up of lines, thousands of strokes, shades, arrows, symbols and more, but behind these lines, intricate and complex systems take place which ultimately brings about a back-and-forth process, what we simply and often call the act of communication through (technical) drawings… Treating the act of drawing as a tool of communication in process also means treating it as a language, which underlines how decisions are made and continue to be made by the people who understand such a language. A reflection on the linguistics of drawings will therefore be made here, through examining how our speech transforms into tangible space and vice versa, with an attempted prevocational drawing about an annotated architecture, the initial struggles of inheriting drawing as a language through architectural education as well as an underlying critique of an industry structured around being able to read the language of drawings.

In order to begin, two concepts which make all languages unique will be taken: grammar and lexicon. At the outset, a blunt description of these two linguistic notions is necessary before delving into the reflection of any drawing type, as the act of representing any matter through visual material is as much a part of communication in itself as any language aims to pursue through written and spoken thoughts. The following points are necessary then, in order to stress as much as possible, the dual application of these concepts and their analogical sense in drawings which are ultimately produced for the architectural realm, for the construction industry and beyond.

Accordingly, the key traits of languages are some of the follows:

1. A lexicon is the collection of all the words in that language, while grammar is a set of rules required for generating logical relations by combining words in a specific structure.

2. We have created such concepts in order to transmit information coherently to ourselves and others.

3. To be the native speaker of a language, means to have absorbed the rules of that language’s grammar and lexicon from birth.

4. Dialects are the differences within a language, which may occur by changes in certain words or structures within different regions.

Reflecting on the first points, architectural drawings suddenly become a mirror image of languages by their ability to act as powerful tools of communication which play crucial elements in the process of creation and knowledge sharing. Keeping in mind the statements above, grammar and lexicon form the pillars of every set of skills needed to materialize a thought for the drafting of a technical drawing. To elaborate, the technical drawing has evolved into a standardized set of elements that are combined, through a widely accepted procedure, to present ideas which can be read and understood by most in the profession. Combining a large number of symbols, lines, hatches and texts, the architect becomes a trained reader of such linguistic tools. Then, in order to evoke fluid interchanges of ideas through drawings, it becomes a pertinent requirement to be using the same language at all times, as one would do so, while speaking any language.

Perhaps now more than ever, discussions around architectural drawings and their ‘domestication’ are gaining stronger momentum, not only by the people within the profession but also by the ones outside of it, partly due to the need for inclusivity, for the ability to be read by all, therefore there seems to be a desire for the reduction of this language to its essence, to something more familiar, legible and comprehensible by the untrained eye. As a result, this demand for simplification and specification could generate new forms of expressions, far from conventional ones. Thus, so-called ‘Dialects’ within the domain of architectural drawings are and have been created in the past centuries in different cultures, which can be referred to as the various drawing styles spread across the globe.

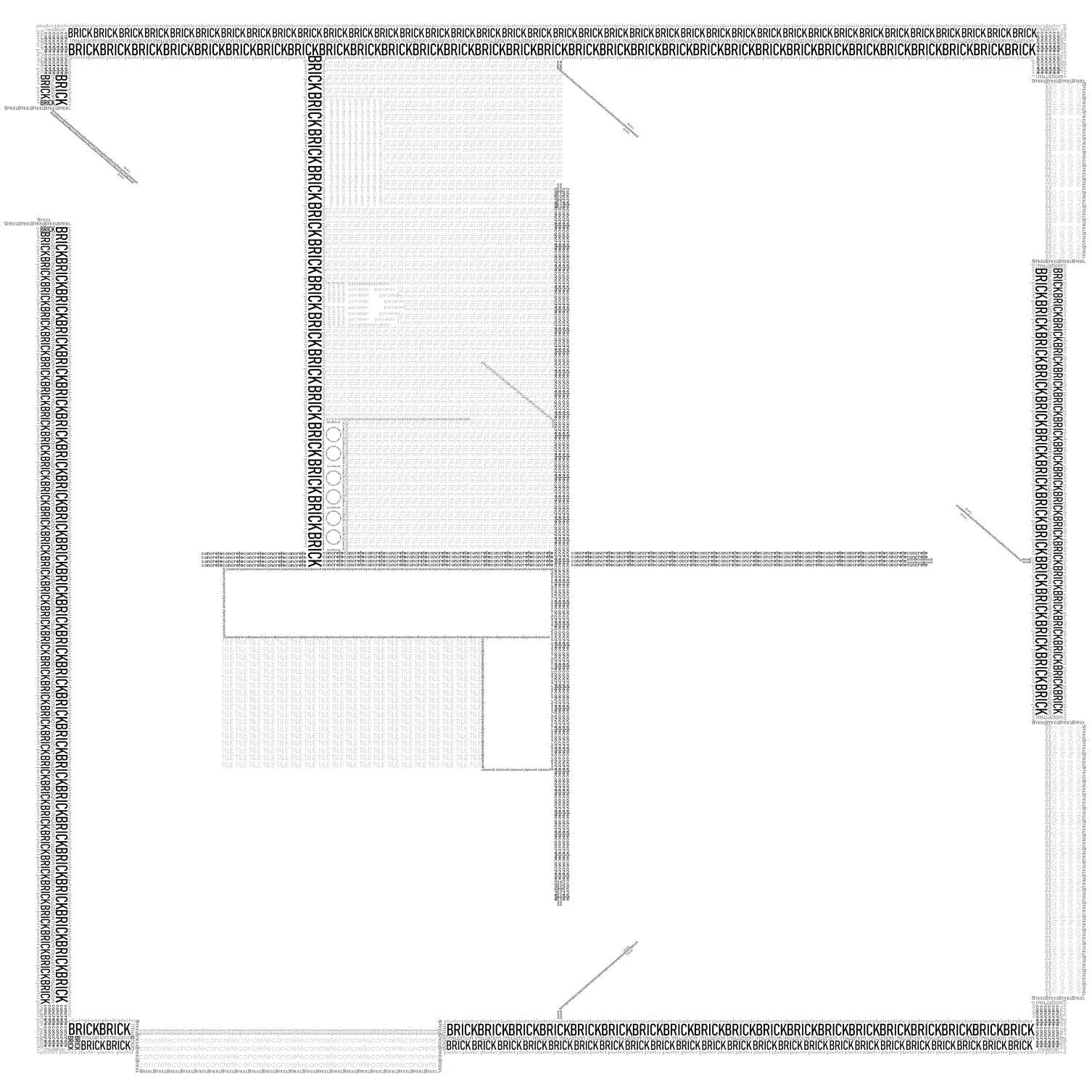

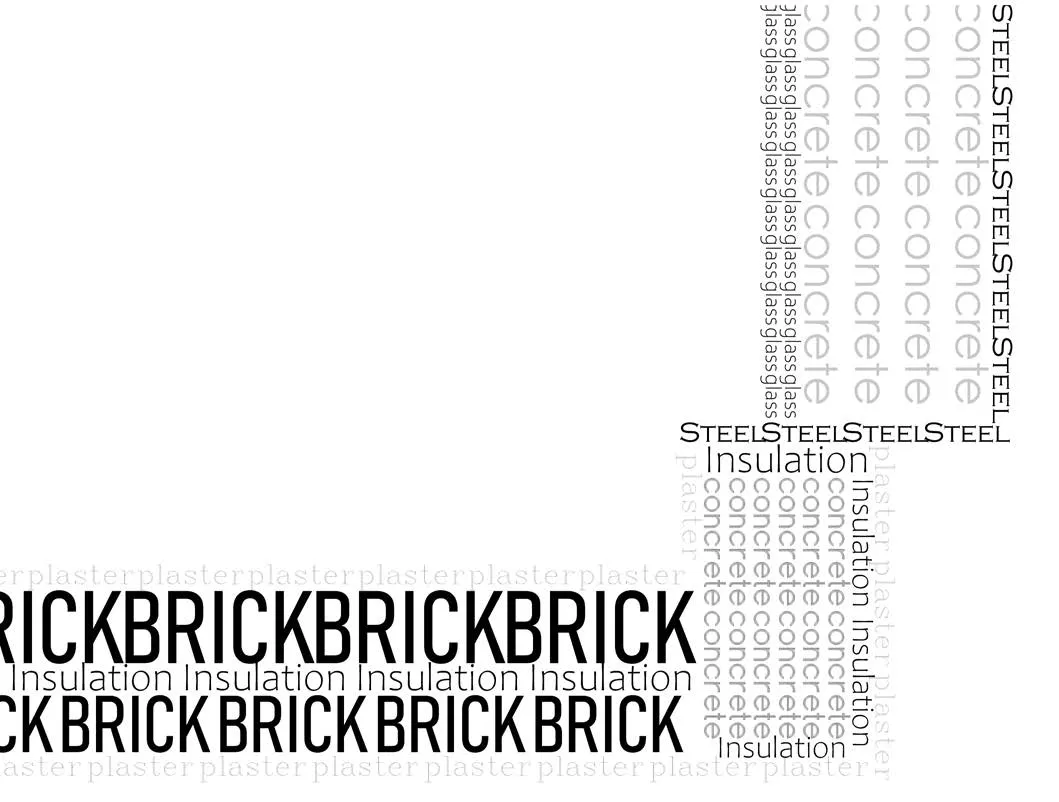

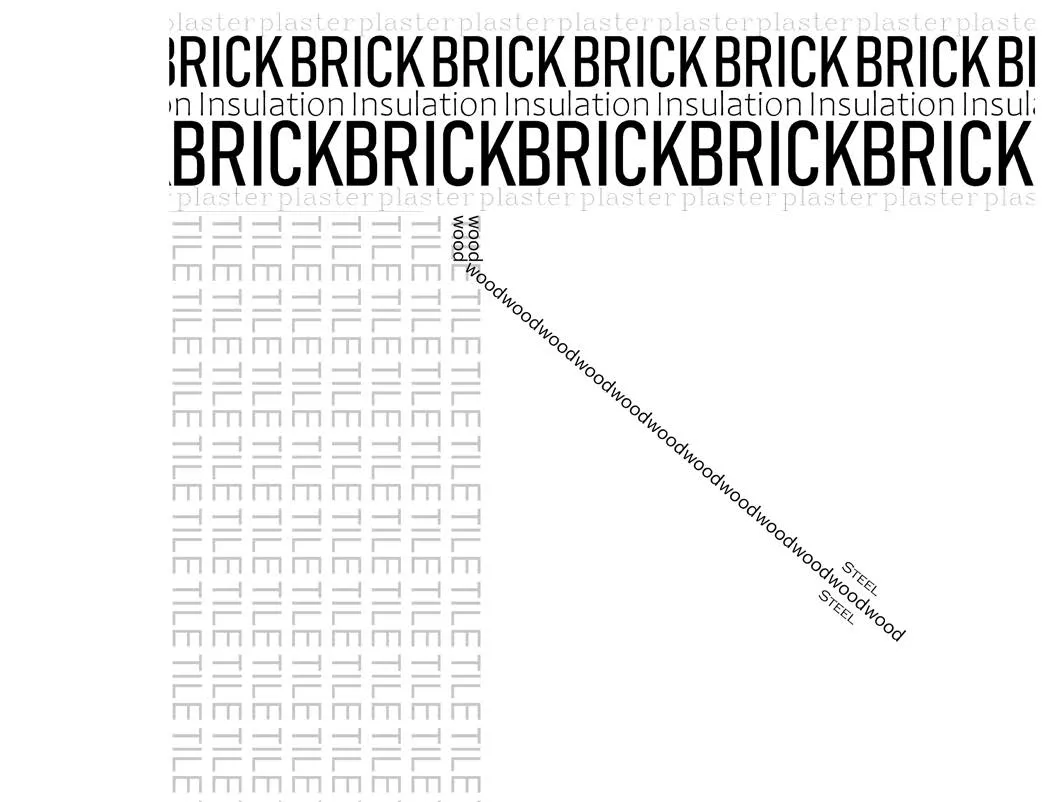

When we begin to simplify a drawing however, a vulgarization of the drawing may occur in this operation. We find ourselves handling a multitude of texts, annotations and arrows in a bid to translate every hatch and line into words. We may ask ourselves, if a drawing was poetry so far, then architectural drawing with such annotations is an explained poem. In the end, it is completely stripped of all its power to be freely interpreted by its reader, while simultaneously gaining a no-longer ambiguous, perhaps uncomfortably dumbed-down meaning. As with everything, today’s capital-based construction industry has taken advantage of this by thoroughly developing its own commercial dialect when it comes to over-describing a drawing. Based on the quantity of annotation required per drawing set, naturally they aim to portray a sense of professionalism amongst the business environment by also becoming more and more specific. The necessity for constant innovation, hence, has increased the need for more specification therefore the amount of text in a drawing. Where do we draw the line between a drawing becoming a text? How many notes are needed to make the annotation a drawing? On the other hand, the potential for a reverse situation periodically takes place. As such, the requirements for self-explanatory notes are now also being utilized as a new, integrated architectural drawing style which can be seen emerging from several practices worldwide. Such drawings, however, purely take the aesthetic values of detailed notes and measurements, without claiming their original use as something that has had functional meaning at one point.

Equally embedded in the language of architecture is the idea that it must first be learnt as any other language, since it is perhaps one of the very few, if not the only, where no one is born a native. Internationally, architectural education established the language of drawing as one of the very first skills that a student must learn in order to communicate ideas to their fellows and educators. However, there is a natural tendency for students to continuously annotate and label their drawings in their first years as they may feel a lack of confidence in mastering their newly acquired language. Fluency comes with practice. Thus, the following drawing is an experimentation in how words transform into the aforementioned lines and hatches, into lexicons of their own, organized in an architectural grammar that is expected to be understood by everyone in the industry. By such a drawing, amongst many questions, one stands out the most: Are there possibilities for other paths in which drawings can be constructed in order to be read and communicated by everyone?

Viktoria Hevesi, Adonel Myzyri

2021

Written for Drawing Matter Competition

No part of this content may be copied, reproduced, or used without permission.