Foreign Manifestation 1970-1975 – Albanian Socialist Architecture

prologue

When the Enver Hoxha Museum was inaugurated on the 80th anniversary of his birth, Albanian socialist architecture seemed to have reached its pinnacle. Some viewed it as a mausoleum where the dictator rested, others saw it as an eagle with open wings, while some regarded it as a forbidden mountain that could not be climbed. However, what stood out most clearly was the stark contrast between the damp walls of the prefabricated apartments and the white marble tiles of the pyramid.

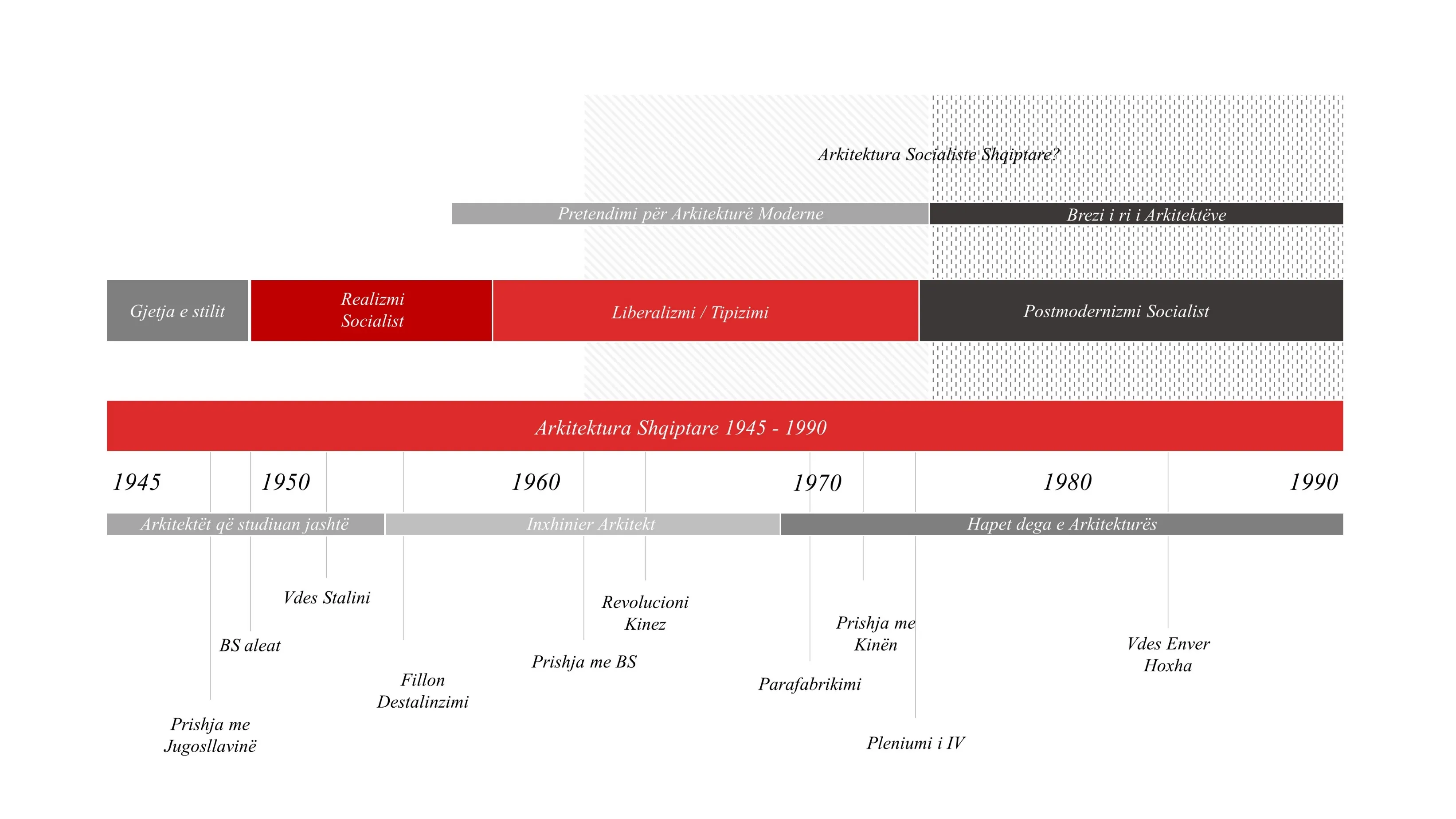

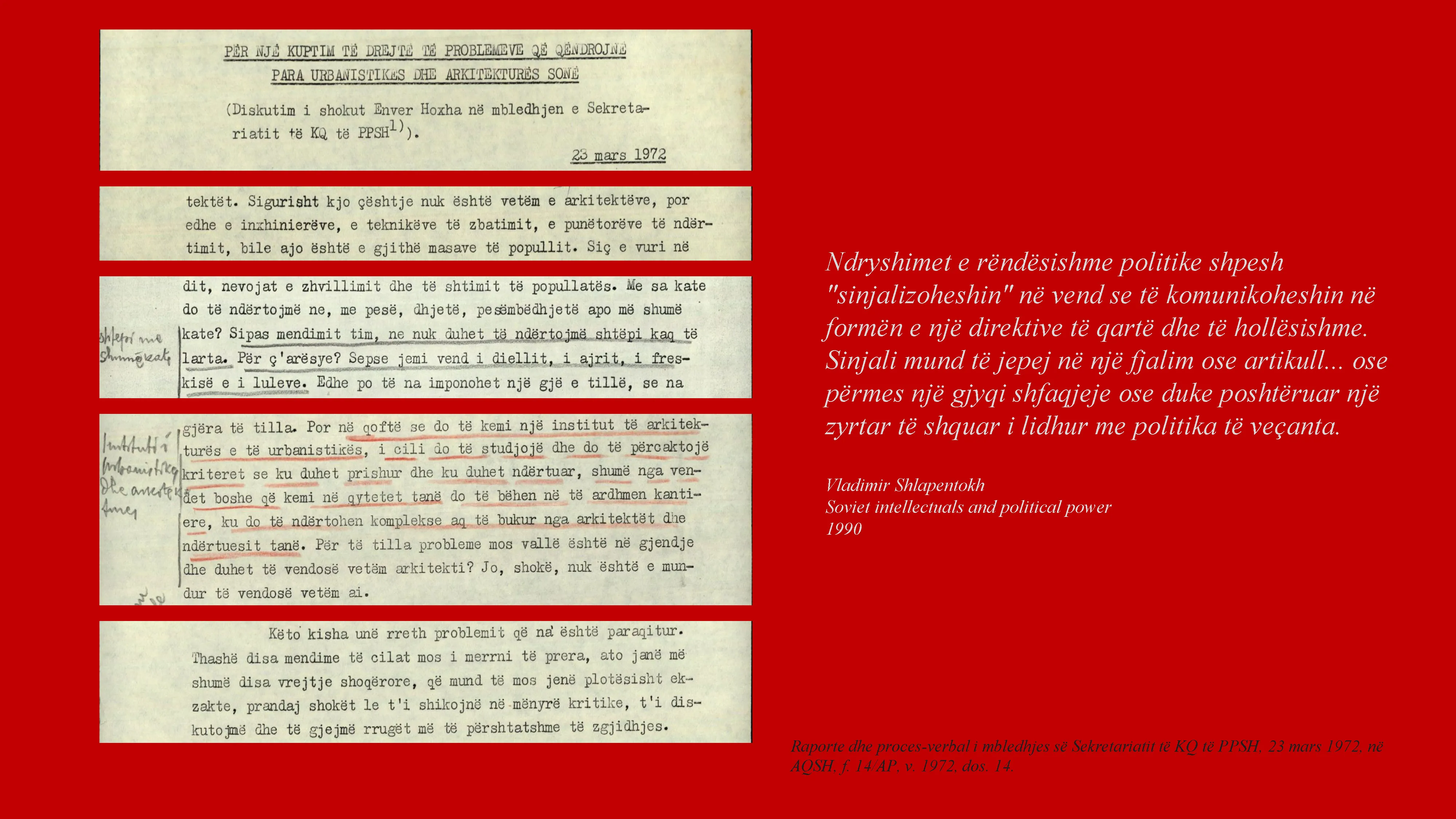

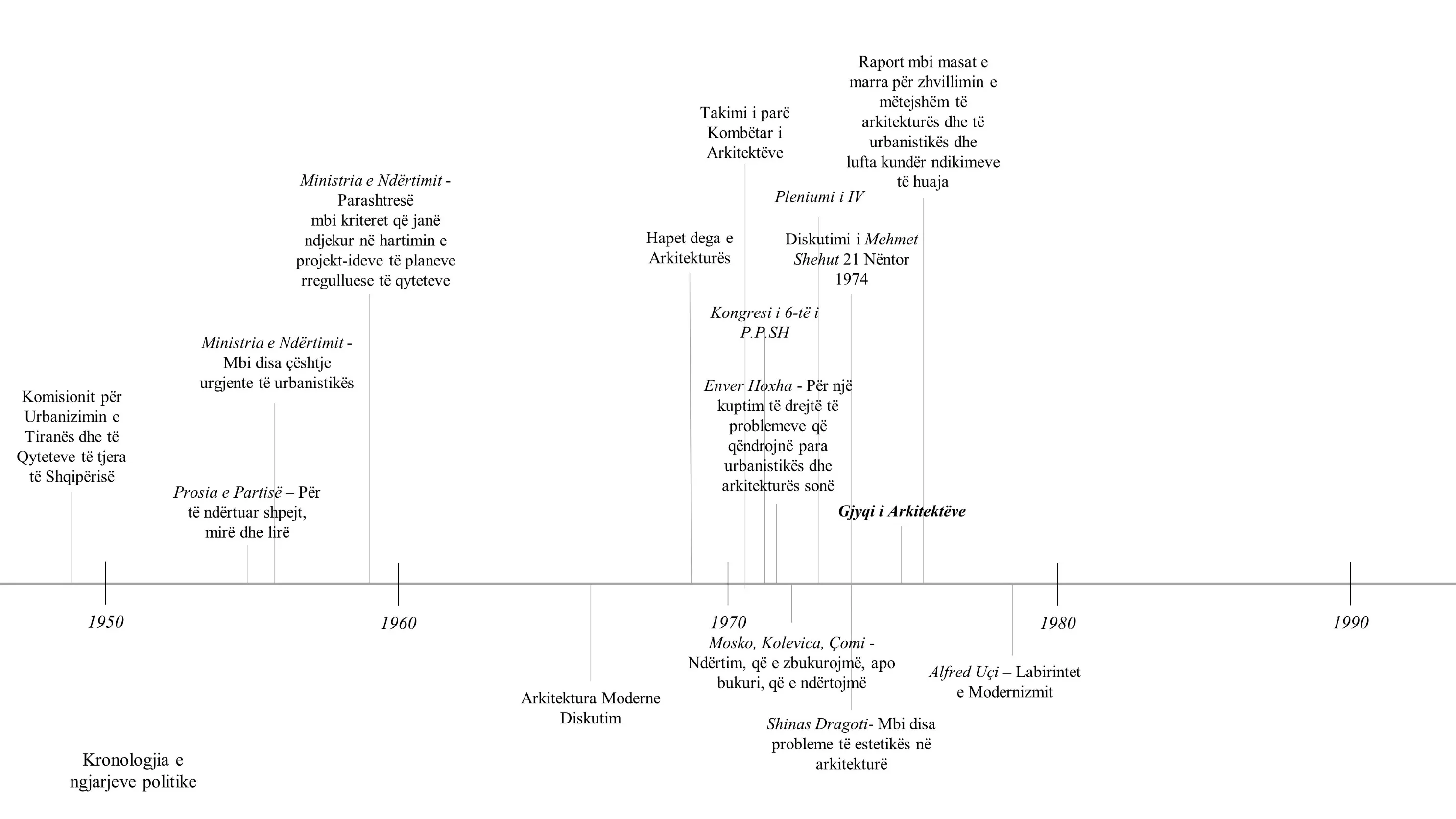

This confrontation with reality would become one of the greatest challenges for Albanian architects in the second half of the 20th century. During this period, the role of the architect in society, as an intellectual capable of critical thinking, did not exist. For the system, the architect was nothing more than a technician, on equal footing with the workers. Nevertheless, there is often a tendency to seek out those architects, if not to heroize them, who, despite repression and isolation, managed to demonstrate high skills and create architecture. Modernism, which according to the communists was a dangerous influence on Albanian architecture, had to be fought at all costs. This stance emerged after the declaration of war against liberalism and foreign influences, with the aim of preparing the ideological ground to withstand the political and economic isolation that followed the break with China. Thus, a widespread ideological cleansing campaign would affect all aspects of life, and for architecture, this would be decisive.

In trying to understand the Albanian socialist architecture, the role of politics as the dictator of ideology becomes evident, while architects were left only with the task of implementing those ideologies. By focusing on and analyzing in detail the events from the First National Architects' Meeting in 1971 to the Architects' Trial in 1975, an effort is made to understand how politics instrumentalized ideology and how the apparatus created specific systems and mechanisms to control architecture. The purpose of this research is to raise the right questions, not to find answers or draw conclusions. What is essential, however, is the critical analysis of architecture as part of a political process, avoiding any aesthetic or theoretical tendencies.

epilogue

In the final chapter of the war against foreign influences in architecture, a new generation of architects emerged from the recently established school of architecture. As Kolevica recalls, "During this time, at the State Design Institute No. 1, one after another, came the daughter and son-in-law of the dictator, as well as four sons and daughters of other members of the PPSH Politburo." Pranvera Hoxha, the daughter of Enver Hoxha, had become engaged to architect and professor Klement Kolaneci; after the events of 1975, Kolaneci would lead the design institute. For Bego and Velo, however, this ideological repression seemed little more than a purge among architects to make way for the new generation.

Equipped with an "ideological passport," this new group would go on to design a series of public buildings, illustrating how "the national" was interpreted in architecture. What stands out most about this moment is the clear division in the history of socialist architecture: before and after 1975. Drawing an analogy to parallel events in global architecture helps us understand that, despite Albania's isolation and drastically different context, opposition to modernism followed a similar trajectory. Globally, modernism was seen as a cause of societal degradation and the loss of traditional values; in Albania, it was viewed as a dangerous bourgeois enemy threatening to erase the national spirit.

If Charles Jencks stated that, “Fortunately, it is possible to date the death of Modern Architecture to a precise moment in time. Modern Architecture died in St. Louis, Missouri, on July 15, 1972, at 3:32 p.m.,” then in Albania, the date of modern architecture’s death (according to architects and historians claims there was modern architecture in Albania, which is yet to be debated to this day) is Enver Hoxha’s speech to the Central Committee in 1972. This extraordinary "coincidence" raises questions: Was it deliberate, or are these parallel realities that never intersect?

In attempting to understand the Albanian socialist architecture, it is impossible to make a critical assessment without asking the right questions. Did modern architecture exist in Albania? What was considered modern architecture in Albania? If so, who were these modern architects? What role did geopolitics play in architecture? What was the role of the architecture school? What defines national architecture? What is considered Albanian socialist architecture?

Andi Arifaj

2019

No part of this content may be copied, reproduced, or used without permission.